Article | Nov 2017 | Workspan Magazine

Salary Compression: The Squeeze is On

Salary compression is once again a challenge for organizations. Here’s what you need to know and how to address the problem.

Editor's note: This article was originally featured in the Nov/Dec 2017 issue of WorldatWork's Workspan magazine.

Thinking about salary compression? You better start! For nearly a decade, stagnant job growth and employees who felt lucky to have a job helped push this issue into the background. Now, the labor market is heating up and the unemployment rate is the lowest it’s been in 10 years. The dangers of salary compression are ready to make a comeback.

Companies are trying harder than ever to entice the best hires, while employees are looking for new opportunities with better total rewards packages. HR departments have to use every possible method available to succeed in the new competition for talent; and in this era of increasing transparency, employees will not tolerate inequitable pay.

What Is Salary Compression?

Salary compression occurs when there are little or no differences in pay, combined with large differences in responsibilities, skill level or qualifications. The inequity may occur between supervisors and subordinates or between new and experienced personnel in the same position. Or it may occur between pay-range midpoints of successive job grades or related grades across pay structures. Take note that compression is rarely a deliberate compensation strategy. And it’s rarely deployed with the intention of encouraging the departure of lower-performing employees. Such a strategy would likely be apparent and damage the company’s reputation.

History has demonstrated that over the long term, companies eventually pay for ignoring problems related to salary compression. For example, let’s look at a physician’s office that has one nurse—a loyal, smart and dedicated employee—who is adored by patients and has introduced many significant cost-saving measures to the practice. The practice is extremely successful and decides to hire a second nurse who will be trained by the star nurse to perform the same work. When the physician’s office discovers no quality candidate is available at the star nurse’s level of pay, it is forced to offer the new employee a 10 percent higher base salary. While this action brings the desired nurse on board, it also makes it necessary to adjust the pay for the existing nurse.

A truly stellar employee can always find a great job. A company that wants to retain its top performers should ensure these employees’ compensation exceeds, or at a minimum, matches the compensation offered to any new hire. If not, the individual employee will almost certainly start looking for a new job once he/she learns of the pay disparity. The increase of a few thousand dollars per year to the existing employee’s base salary is quite small in comparison to what it would cost to recruit, hire and train a replacement—one that may not have the same star qualities.

A Peek at Market Trends

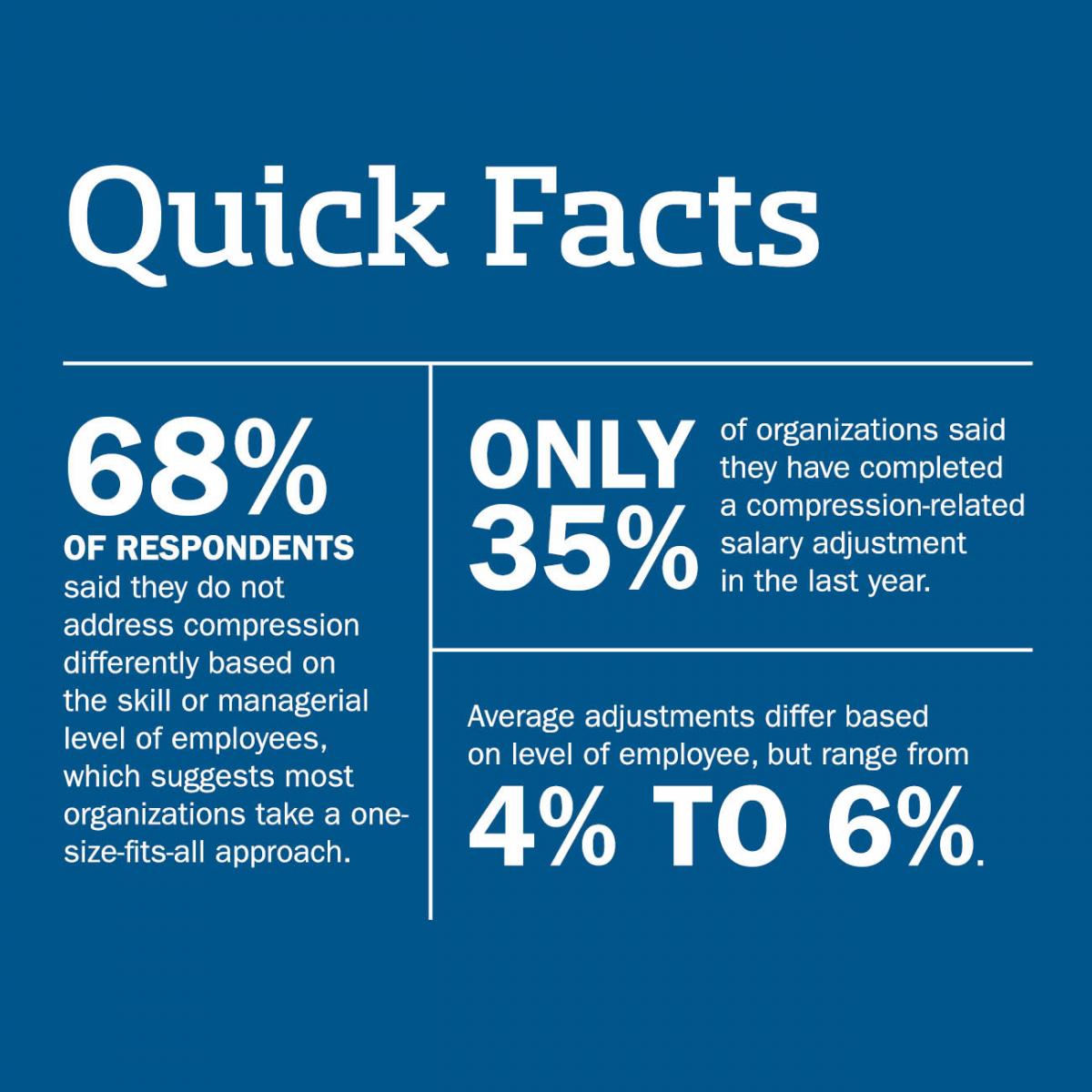

An August 2017 Pearl Meyer survey, “Salary Compression Practices in the United States,” offers insight to companies’ experiences dealing with compression issues.

The survey found salary compression to be most common in IT and engineering/science jobs, where technology and in-demand skill sets change rapidly. More than 60 percent of companies indicated compression occurs because those positions that require “hot skills” force the company to raise starting salaries to attract the right talent. Because these companies have a constant need for technical talent with the latest skills, such as programming and application development, cyber security and artificial intelligence, companies are ready to offer premium pay to new employees who have the specific technical expertise, even if they will be performing essentially the same jobs as lower-paid incumbents who may not have a similar skill set. In such situations, compression often is accepted as a lesser evil to failure to bring desired candidates on board.

However, the practice of bringing new employees in at a higher rate without an increase for current employees can put the company at risk for losing existing talent. Eighty percent of survey respondents said that salary compression has either a high or moderate impact on employee retention. Three trends, based on culture, economics and geography, are driving this issue:

- Pay Transparency. If you think that employees don’t know how much their peers earn, think again. More than a third of organizations said that pay transparency is a matter of concern at their organization. Millennials make up an increasingly large portion of the workforce, and they are changing the culture around income and privacy. Millennials share salary and bonus information with their colleagues, friends, and even strangers on social media or employer-rating websites. Be aware, employees will find out, either first- or second-hand, if they are being unfairly paid.

- Minimal Annual Salary Budgets. More than 75 percent of companies experiencing compression have longer-term employees that started with lower salaries, and their annual increases have not kept pace with current market demands and/or inflation. Pearl Meyer’s annual “Compensation Planning Survey” has reported annual salary budgets of no more than 3.1 percent in the past five years. This trend of flat salary growth is a major contributor to salary compression.

- Location. Salary compression is most palpable at the regional level. While pay inequity certainly exists in companies that span multiple states or countries, factors such as employees’ lack of direct exposure to peers in far-off sites or cost-of-living variances often smooth out the destabilizing effects.

One clear example of regional salary compression is occurring in the Northeast. One factor is these states’ continual increase to minimum-wage rates above the national rate of $7.25.

- Connecticut – $10.10

- Maine – $9, soon to be $10

- Massachusetts – $11

- New York – $9.70 and soon to be $10.40

- Vermont – $10 and soon to be $10.40

As Northeast states continue to increase wages, the changes in pay can create inequities within the region if companies fail to also adjust compensation levels for employees who were previously earning at, or slightly more, than the previous minimum wage.

Although compression tends to be more common at lower levels, it can happen throughout the organization. For example, let’s look at a company expanding its cybersecurity executive group. The company finds two excellent candidates and extends offers that are low in the position’s salary range to both. The first candidate is excited about the offer and accepts the job immediately. The second candidate advocates for himself/herself much more strongly and negotiates a starting salary near the top of the pay range. After they are both fully trained and productive contributors, it becomes clear that the lower-paid candidate is a far superior performer than the higher-paid individual doing the same job. Now, it’s only a matter of time before the top performer will find out about the pay disparity. In order to keep that individual, the company must adjust his/her pay.

Avoiding Compression

The emergence of pay transparency and changes to the minimum wage are certainly not within the control of human resources. Companies can, however, manage internal factors related to compression such as merit-increase programs, hiring practices, and salary structure guidelines. Following are four practical approaches to preventing compression:

1. Communicate Broadly

- Be transparent with pay. From the perspective of the employee, there is nothing worse than finding out second-hand that you make less than one of your peers doing the same work. More than ever, organizations are following the lead of companies like Whole Foods, which makes compensation information for all staff available to every employee. It is nearly impossible for salary compression to occur when every employee knows what his/her peers, managers, and subordinates make. Sharing all compensation information is at the far spectrum of pay transparency. Organizations that are not ready to go this far can take smaller steps to make pay determinations clearer to employees.

Traditionally, the compensation department has been a “black box” to employees. More than a third of organizations surveyed said their employees don’t have an understanding of their company’s compensation philosophy, strategy, and practices. Organizations can address this by making it a point to fully inform employees about the pay practices and how pay is determined. As many companies have discovered, a perception that people are being compensated unfairly can be as damaging to employee performance and morale as actual pay inequity. Knowing their company recognizes and is using tools and procedures to avoid problems with compression reinforces employees’ confidence that their own pay is fair. - Educate managers. Hasty, reactive hiring decisions made to quickly fill vacancies often result in salary compression. The HR department can address this issue by clearly communicating the organization’s pay strategy and philosophy, so that management appreciates the multiple negative effects of salary compression in the workplace. At a more fundamental level, managers should be educated on the ramifications of this issue, such that it enters into their hiring strategy.

2. Use a Range of Compensation Components

- Sign-on bonuses. Along with serving as one of the most effective enticements for job candidates to quickly accept a position, sign-on bonuses reduce the potential for pay compression by providing new hires with a one-time-only premium payout, rather than an ongoing compensation premium.

- Variable pay. Wisdom dictates that a higher salary will only motivate someone until he/she gets used to it. Incentives, on the other hand, provide an ongoing aspirational target. Similar to sign-on bonuses, cash incentives tied to performance metrics offer high performers an opportunity to earn more without creating base-pay compression. They also tend to draw a straight line between achievable metrics beneficial to the organization and the rewards available to the employee.

- Performance-based merit awards. Merit pay increases for top performers should be sufficiently significant to alleviate or avoid compression. And much like variable pay, they should have clear and reasonable metrics by which they are achieved. Too often, organizations with a 3 percent per-annum merit increase use a peanut butter approach to evenly spread funds to most or all employees. A better approach would be to give no increase to poor or below-average employees, one to two percent to average employees, and five to six percent to top performers.

- Nonmonetary rewards. Nonmonetary benefits are increasing in popularity and carry the advantage of creating value for the employee, often with little or no concrete cost to the organization. Programs like teleworking, community-service days, and on-site chair massages offer relatively low-cost ways to enhance the total rewards package without increasing pay.

3. Monitor the Market

- Salary structures. Making appropriate salary structure adjustments each year ensures midpoint differentials are not too narrow, which allows for sufficient salary growth from one level to the next.

- Market competitiveness. Keeping up-to-date on market rates helps ensure pay is competitive and the placement of positions makes sense within the salary structure. Market-based compensation surveys can help organizations ensure rates are in line with labor market competitors. This can assist with the establishment of internal compensation metrics, as well as with recruitment or retention strategies, especially in highly competitive or subspecialized labor markets.

4. Adjust as Necessary

- Off-cycle merit adjustments. Adjusting pay rates for key personnel throughout the year in response to market forces or changes in the objective value of employee contribution—rather than limited changes to once annually—is a policy many companies find to be an effective and proactive approach to avoiding salary compression. Off-cycle merit adjustments can be used at all levels in the organization, although they are most often used for new college graduates in disciplines where pay has increased faster than average overall merit increases.

- Lump-sum merit awards. It’s common for long-tenured incumbents to be “red circled,” or paid very high within the salary range, resulting in salary compression if their pay exceeds that of incumbents in higher-level positions. This is typified in many government or unionized organizations. Lump-sum merit awards allow employers to recognize and reward the performance of highly paid employees without causing compression.

Know the Risk

Salary compression can quietly develop over time, building its own negative momentum and catching organizations by surprise. Companies that are struggling financially or those seeking to eliminate every last cent of expense may be tempted to brush salary compression issues aside as something to be addressed another day. However, there is a real and growing risk—due to the increasingly hot job market—that this strategy may backfire. It is clearly more expensive to hire than it is to retain, as it consumes management and recruiter time. Further, losing key employees affects organization morale, jeopardizes ongoing projects and programs, and increases the workload and stress among those remaining. The challenge is to avoid paying higher wages to a potentially lesser applicant.