Article | Jun 2021

Compensation Peer Group Development in an ESG World

Exploring the business case for including a company’s ESG impact in its peer group development

COVID-19, a polarized political environment, social unrest and the Black Lives Matter movement, climate change and increased weather volatility. The impact of these developments on humans over the last year has been profound.

Developments across the Environmental, Social, and Governance or “ESG” landscape focus on understanding and quantifying the various factors, like those noted above, that directly and indirectly affect our lives.

For boards, and particularly compensation committees, that are exploring ESG, a question to consider is whether the peer group development process should evolve to better reflect the company’s ESG impact. The business case for considering a company’s ESG impact in peer group development is strong:

- Recent statistics suggest that roughly 1/3 of US-based invested assets (~$17 trillion) are managed under Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) mandates where investment criteria explicitly include ESG factors.

- The SEC recently adopted new principles-based rules requiring disclosure of Human Capital Management (HCM) strategies and objectives that a company focuses on in managing its business.

- For more than 20 years, the Business Roundtable maintained the position that corporations existed to primarily serve shareholders. That changed in August 2019 with the release of a new set of Principles of Corporate Governance that endorsed the idea that corporations should serve all stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, and communities, as well as shareholders.

If one accepts the idea that competition for investor capital is a valid peer selection criterion, that business strategy comparability may be used to screen for peers, or that businesses should serve constituencies beyond shareholders, then it stands to reason that companies cannot ignore their impact on their workforce and society more broadly and ESG factors should be considered in the peer selection process.

History of Peer Group Development

Before prognosticating on how peer group development processes may evolve to reflect ESG, it is helpful to understand how we have arrived at the current peer group selection norm.

The peer group development process has gone through considerable change over the past 30 to 40 years. Historically, statistical analysis on the relationship between executive pay and other variables revealed that revenue within a given industry (outside of financial services) was the strongest predictor of pay, and the strength of the relationship between other variables and executive pay was modest at best. This was, and continues to be, applied as a blunt instrument in the peer selection process.

The lack of institutional scrutiny on executive pay for a time also led some companies to use “aspirational” peer groups. These were generally comprised of large, strong-performing companies and their use reflected a belief that you had to pay like those companies if you wanted to become one of those companies.

Over time, the “network effect” has played a larger role in peer group construction. Today, standard peer group development processes include an understanding of two primary network drivers: 1) which companies consider your company a peer and 2) which companies are in the peer groups of your peers. One of the main proxy advisors explicitly incorporates the network effect in peer group construction.

Finally, over the past 10 years, companies are more likely to maintain multiple peer groups—one peer group for compensation analytics where size comparability is important and one peer group for performance analytics where tighter performance comparability is required.

Some companies do consider other factors, such as EBITDA reflecting the ability to pay, market capitalization as an indicator of the value of the business managed, or enterprise value as an indicator of the value of the business managed independent of capital structure. In specific industries, the number of sites or locations may also be considered. Generally, these factors are subordinate to revenue (or assets) as the primary size selection criteria.

One constant in the peer development process remains: peer group development generally starts and ends with revenue or a comparable size metric.

Impact of ESG on Peer Group Development

In any model where ESG is explicitly considered as part of the peer group development process, there are two key questions that must be answered:

- How should ESG comparability be positioned against more conventional filtering criteria; and

- What specific ESG factors should be included in peer selection criteria?

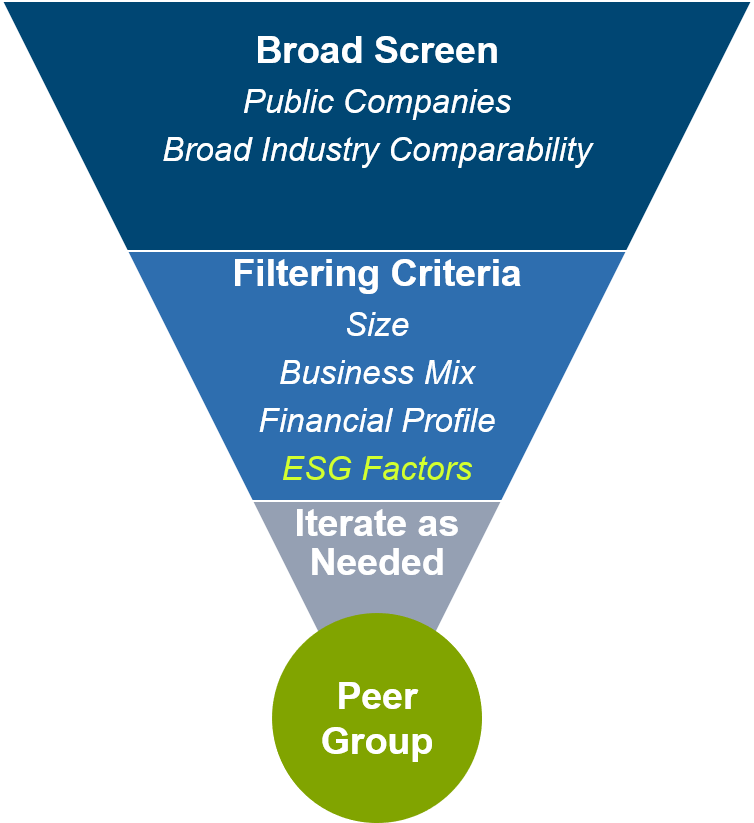

Peer group development is about identifying a group of companies against which pay and performance can be reasonably compared. It requires balancing various peer selection criteria to arrive at a peer group of a sufficient number of companies—ideally, at least 15.

For most companies, the core process for peer group development probably does not change and ESG comparability does not supplant existing peer selection criteria like industry, revenue or assets, and market capitalization or enterprise value. Peer groups must still pass an industry-based “sniff-test.” However, ESG’s importance in peer group development may be emphasized to a greater degree than it has been in the past.

We see the ESG impact showing up in peer group development in two specific ways:

- Peer group selection criteria expands beyond conventional filtering criteria to specifically include ESG comparability. As shown in the peer filtering process at right, ESG factors are explicitly included in the peer development filter and are balanced against other relevant filtering criteria.

- Variances in peer comparability on conventional filtering criteria become more acceptable if there is greater comparability on ESG factors. In normal peer group development processes, we occasionally reach the point where identifying additional peers to ensure we have a sufficient number of companies becomes challenging due to lack of comparability on the conventional criteria. In these situations, inclusion of certain companies may be justified based on comparability of ESG factors.

First, determining which ESG factors should be included in the peer selection criteria presents some challenges as there are no consistent disclosure requirements across the various ESG dimensions (including the new HCM disclosure requirements noted above). So, while many companies can quantify their own ESG impact, the lack of easily-accessible and consistent disclosure requirements makes filtering on ESG comparability significantly more challenging.

Second, the universe of ESG dimensions is extensive and reducing ESG impact to a single comparative basis for peer group selection may oversimplify what in reality is very complex. It may be more convenient to focus on specific ESG dimensions that are most relevant to a given company and using that to screen for potential peers. For example, a company operating in the gig economy may screen for companies where there is a similar comparability, risk, and exposure around labor practices.

Ultimately, the specific ESG factors that may be used in peer group development are going to be very much facts- and circumstances-based. Companies would be expected to filter on potential peers that that have a similar ESG risk, based both on the dimension and the quantum.

Example: In the short term, as companies work to better understand the broader ESG landscape and given data challenges to effectively compare ESG impact, there may be shortcuts available. For example, one strong-performing S&P 500 client in the financial services sector with the following fact base makes a compelling case to overweight comparability on number of employees:

In this situation, management believes there is a strong case that the companies with higher revenue but more comparable total number of employees is more appropriate if ESG is specifically considered in the peer group development process. |

New reporting requirements and consistent disclosure standards on ESG factors—and climate-related risk specifically—are clearly early priorities under the Biden administration and an SEC led by Gary Gensler. The EU, and the UK (as it did with say-on-pay), provide an early model to potentially follow as new ESG disclosure requirements come into play for accounting periods starting in 2021. Any new SEC disclosure requirements would allow companies to get more clarity on ESG comparability and in time it will become easier to consider ESG factors in the peer selection process.

In Summary

It is clear that ESG issues are here to stay and will only play a larger role going forward. Early movers have built very specific ESG hurdles, such as diversity and inclusivity and carbon dioxide emissions, into their incentive plans. At the same time, other companies who are not as far along on the ESG journey continue to discuss the role of ESG in business strategy and whether ESG should be explicitly measured for incentive compensation purposes.

In any case, as early adopter companies have determined there are compelling reasons to include ESG considerations in incentive plan design, it is clear that there are opportunities to build ESG considerations into other elements of a company’s overall compensation strategy.