Article | Dec 2019

Balancing Credit Union Executive Incentives When There is No Stock to Share

Credit unions often rely on SERPs as executive retention tools; here’s why and how to implement more performance-oriented long-term incentives.

Why are Supplemental Executive Retirement Plans (SERPs) the only form of long-term compensation offered at most credit unions? SERPs are an important tool in a company’s executive retention plans, particularly when equity is not an option. However, they help retain executives whether the executives are performing or not. As credit union members become increasingly educated about these matters, they may begin to ask the board about long-term incentive (LTI) compensation tied to organizational performance that is in the best interests of the members.

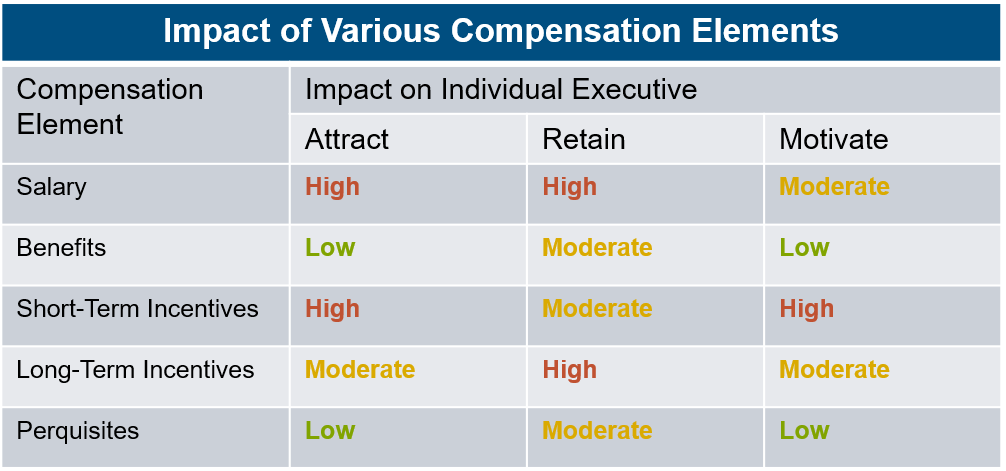

It takes a mix of compensation components to attract, retain, and motivate an executive’s balanced performance. For most public and many private companies, stock-based incentive plans are the most common form of LTI. For credit unions, and some other mutual cooperative organizations, there is no stock to be shared, yet that is not reason enough to forego performance-based LTI, as most credit unions do.

Instead, SERPs have emerged as the industry’s primary long-term form of compensation. Such plans tie the executive to the credit union by promising to plug the gap in retirement funds created by ERISA and IRS rules that govern the tax advantaged qualified retirement plans. This executive benefit is in widespread use in all sorts of organizations, even those that offer stock-based LTI, since the two types of plans serve different purposes in the compensation mix. The SERP promises to enable an executive to retire on the same percentage of their final salary as other employees, and the LTI plan (or LTIP) supports the accumulation of wealth. One provides the bread, butter, and mortgage money and the other is about travel and entertainment during the executive’s later years, as well as leaving something for the estate.

LTIPS are extremely rare in credit unions. There are two primary reasons for this:

- Since there are no shares of stock in credit unions, some form of synthetic shares is usually considered, and then often rejected because they can be a bit complicated; and

- The world is changing so fast that it is difficult to set performance goals more than a year or so in the future.

Are synthetic shares all that complex? Think of the synthetic shares as units of value. That value need not be tied to the credit union’s net worth. They can simply be a way of keeping score. However, there is something elegant about tying the units—often called phantom shares—to the net worth of the credit union. Let’s look at that model.

Let’s say your credit union’s net worth is $25 million. We could say that we want one unit or phantom share to equal $10 of value. Therefore, we can say that the credit union has 2.5 million units ($25,000,000 of net worth ÷ $10 per unit = 2,500,000 units).

Now, the compensation committee resolves the following questions:

- What long-term goal do we want to achieve and what will it be worth? Since credit unions have few options for raising capital to support growth, practically speaking, increasing net worth by growing earnings must be done to support deposit and asset growth.

- How much net worth will the credit union need to have three years from now? Continuing with our $250 million credit union example, we are projecting that we will have $300 million of assets by the end of three years. Of course, this will be determined by careful strategic planning, but for our example, we set two goals to be measured after three years:

- To grow assets to $300 million in three years; and

- To maintain average annual equity as a percent of assets at 10%.

- How much potential reward will be required to keep the focus on building assets and net worth toward the goals? Remember, the payout will be three years out. Remember, too, that the plan must be affordable while we are still trying to grow net worth.

The compensation committee must then determine which executives will participate in the LTIP and how the potential awards will be earned. In our example, we might award the number of units based on the asset growth, and since the units were valued as a percent of net worth, the units will grow in value as net worth grows in value. Of course, if the credit union’s assets do not grow and net worth does not grow, the value of the units will not grow either.

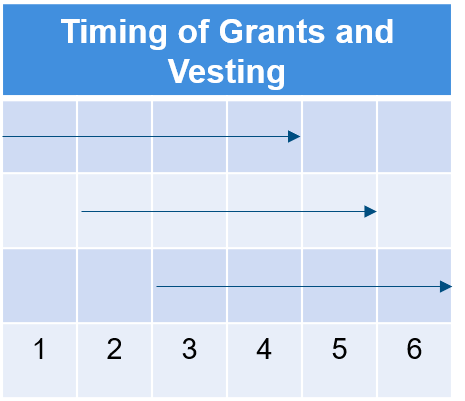

There is considerable flexibility here. Plans can reward only the appreciation of the units’ value, or they can reward the total value of the units. That design feature depends on the overall objectives of the plan. Rewarding the whole unit value after it vests helps retain executives even during hard times when there is not much appreciation in assets and net worth. However, awarding only the appreciation in the value makes it a pure pay-for-performance plan. Most LTIPs grant a series of three-year opportunities and make annual grants of units that vest at the end of each three-year period (see “Timing of Grants and Vesting”). There are plenty of other long-term metrics you can mix in as well, like Net Promoter Scores and other measures of member satisfaction.

Long-term incentive plans that pay extra for achievement of strategically important objectives likely belong in any executive compensation package, no matter the organization’s ownership structure. Without this component, there is no balance and there is a tendency to develop a focus on short-term thinking. This is especially true when all incentives, from annual salary hikes to annual cash incentives, are being used. This often leads to being the last to market with new products and services, a hesitation to close a dying branch and open a new branch, and/or a reticence to invest in developing talent. A “no-risk” way of thinking sets in.

Of course, incentive plans cannot overcome a culture that does not support accountability, but where there is a desire to link compensation to achievement of strategy, properly designed long-term incentive plans can make a difference. Just because a credit union does not sell stock to raise capital does not mean there is no place for LTIPs. In fact, it may mean credit unions need LTIPs more to spur performance than a stock-based organization whose shareholders will demand it.