Article | Sep 2019

Are Incentive Stock Options Worth the Trouble?

Tax reform has renewed interest in incentive stock option grants. There are some positive benefits, but the details are complicated.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017 (TCJA or 2017 Tax Reform) dramatically lowered federal corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%. In addition, 2017 Tax Reform revised the individual alternative minimum tax (AMT) computation with higher AMT income exemption amounts and a higher income point where the phaseout starts. As a result, we’ve been finding more interest—particularly by start-up and private equity companies—in granting incentive stock options (ISOs).

Like nonqualified stock options (NQSOs), ISOs allow holders to buy stock at a specific price (the exercise price) for a given time period (max of 10 years for ISOs). With both types, when the company stock price rises above the exercise price, the stock option has value.

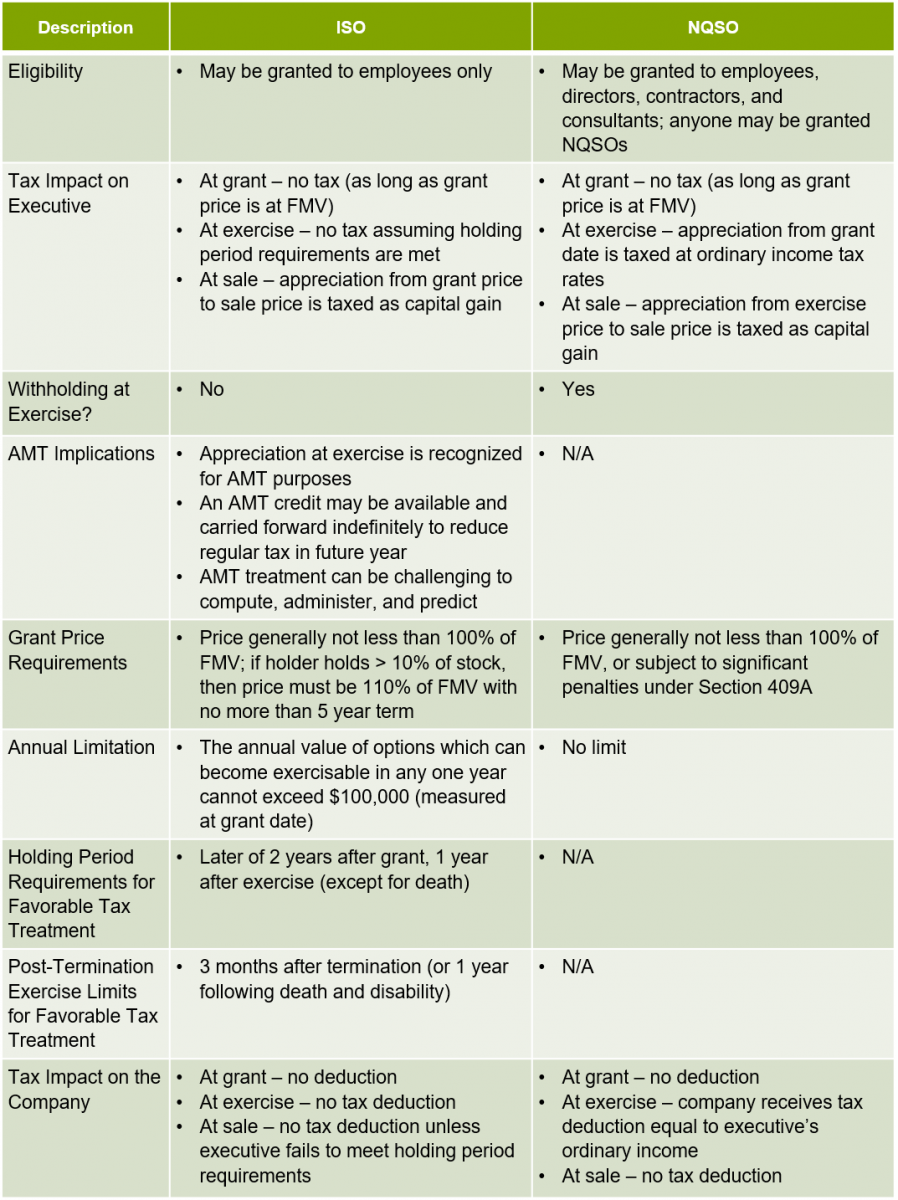

But ISOs also carry the promise of preferential tax treatment. While a NQSO is taxed at exercise at ordinary income tax rates (and subject to employment tax withholding), no tax or withholding is required when an ISO is exercised. If statutory holding periods are met, ISO holders may be able to defer taxation until the sale of the stock, with any appreciation (from grant to sale) taxed at favorable long-term capital gains rates. An overview of some of the major differences between ISOs and NQSOs can be found in the chart below.

Despite all the good press about ISOs, there are a few reasons that ISOs might not be the optimal choice.

First, ISOs are far more complex than NQSOs.

ISOs must comply with numerous statutory requirements in order to receive favorable tax treatment. If ISO requirements are not met, or are inadvertently violated, the option is taxed as if it were a NQSO. Some of the conditions include: two holding requirements must be met (stock must be held at least one year after exercise and two years after grant); the annual value of ISOs which can become exercisable in any one year cannot exceed $100,000 per individual; and if the holder terminates employment, ISOs must be exercised no more than three months after termination. These and a host of other complexities make ISOs difficult for companies to administer and confusing for employees and employers.

Next, because of AMT, the true tax implications of ISOs are difficult to project.

ISOs are considered NQSOs for AMT purposes and, once exercised, the spread between the fair market value (FMV) of the stock and the exercise price is added to income when calculating AMT. As a result, many ISO holders are surprised (and confused) by AMT tax in the year of exercise. (We can’t overemphasize how much AMT complicates and confuses matters for all but the most skilled tax geeks.)

While an employee may be entitled to an AMT credit that is carried forward to reduce regular tax in future years, there are no guarantees that the credit will be utilized as the ability to use the credit is highly dependent upon a taxpayer’s individual facts and circumstances in the future. And while Tax Reform may have reduced the number of individuals encountering AMT problems, projecting future tax results remains onerous…and unpredictable.

Significantly, more often than not, the potential tax benefits of ISOs are not realized.

Many ISO holders sell their stock early and don’t end up ever meeting the holding requirements for one reason or another (these sales are known as “disqualifying dispositions”) or an employer enhances or modifies the terms of an award so that the ISO is treated as a NQSO (known as “material modifications”). For example, this happens when post-termination holding periods are extended beyond required statutory limits.

It’s also common for stock plans to call for accelerated vesting in the event of a change-in-control (CIC) or for certain qualifying terminations such as death or disability. Vesting needs to be managed when administering the $100,000 limit, so if vesting of an award was already being maxed out to reach the limit, the additional accelerated shares will become NQSOs.

And finally, the obvious: companies lose tax deductions on qualifying dispositions of ISOs.

While the spread on exercise of NQSOs is tax deductible, if ISO holding requirements are actually met, the company receives no tax deduction. And although Tax Reform has lowered corporate tax rates significantly, companies still need to consider lost tax benefits in their analysis, if material. However, for certain executives whose taxable income exceeds $1M, NQSOs may not be deductible under IRC Section 162(m); in these cases, the lost tax deductions for ISOs would not be a concern.

Conclusions

While ISOs are structured to provide employees with preferential tax benefits, these benefits are not often realized for a variety of reasons. When the associated complexities and lost tax benefits are also considered, ISOs may prove to be more trouble than they’re worth.