Article | Sep 2022 | Workspan Daily

A Fresh Look at the Much Debated “Last-Minute” Excise Tax Gross-Up

Providing an excise tax gross-up is sensitive for boards, given its poor reputation. Here is data providing a clear picture of the practice.

Under pressure from shareholders and their advisors, companies have been eliminating excise tax gross-up provisions from legacy change-in-control (“CIC”) and severance agreements since the late 1990s.1 Many companies removing gross-ups pledge not to include them in any new agreements going forward. But despite the promises, some companies end up adopting these in anticipation of a CIC or other strategic transaction.

The decision as to whether to provide an excise tax gross-up is always a sensitive one for boards, given the vehicle’s poor reputation. In the context of a merger or acquisition, compensation committee members often need answers to the following questions:

- How common is it for companies to agree to new excise tax gross-up protections in the deal context and how costly are they, typically?

- What is the rationale for companies choosing to adopt these?

- Has implementing new excise tax gross-ups impacted corresponding “say-on-golden-parachute” (“SOGP”) advisory vote results?

To provide a clearer picture of the practice, we summarize activity on “last-minute” excise tax gross-ups, obtained by Pearl Meyer and Main Data Group from say-on-golden-parachute disclosures in transaction filings from 2016 to early 2022.2

50 “Last-Minute” Excise Tax Gross-Ups

In a study of over 900 transaction disclosures, we identified 50 examples of companies (without excise tax gross-up provisions before a CIC) adding one or more of these entitlements shortly before the closing of a transaction. The examples we found were in SOGP disclosures from transactions occurring between 2016 and early 2022. The count of 50 includes companies that disclosed the right to provide excise tax gross-ups (to one or more executives) as well as those that implemented the entitlements.

Out of the 50 companies/transactions, 40 underwent and reported a SOGP advisory vote, while 10 companies were not subject to the vote.

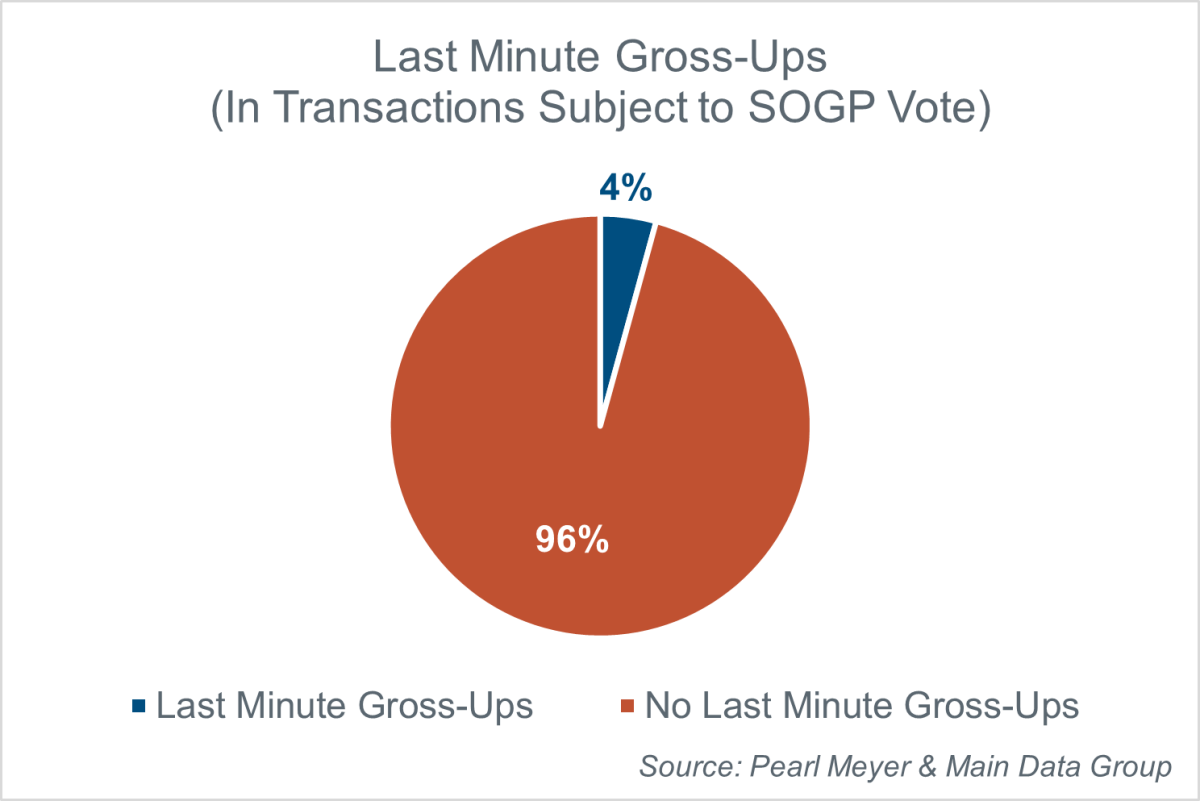

Although providing last-minute gross-ups has grabbed the headlines, it appears to be a minority practice—only 5% of the entire study group (4% when considering just the companies subject to a SOGP vote) implemented these at the time of the transaction filing.

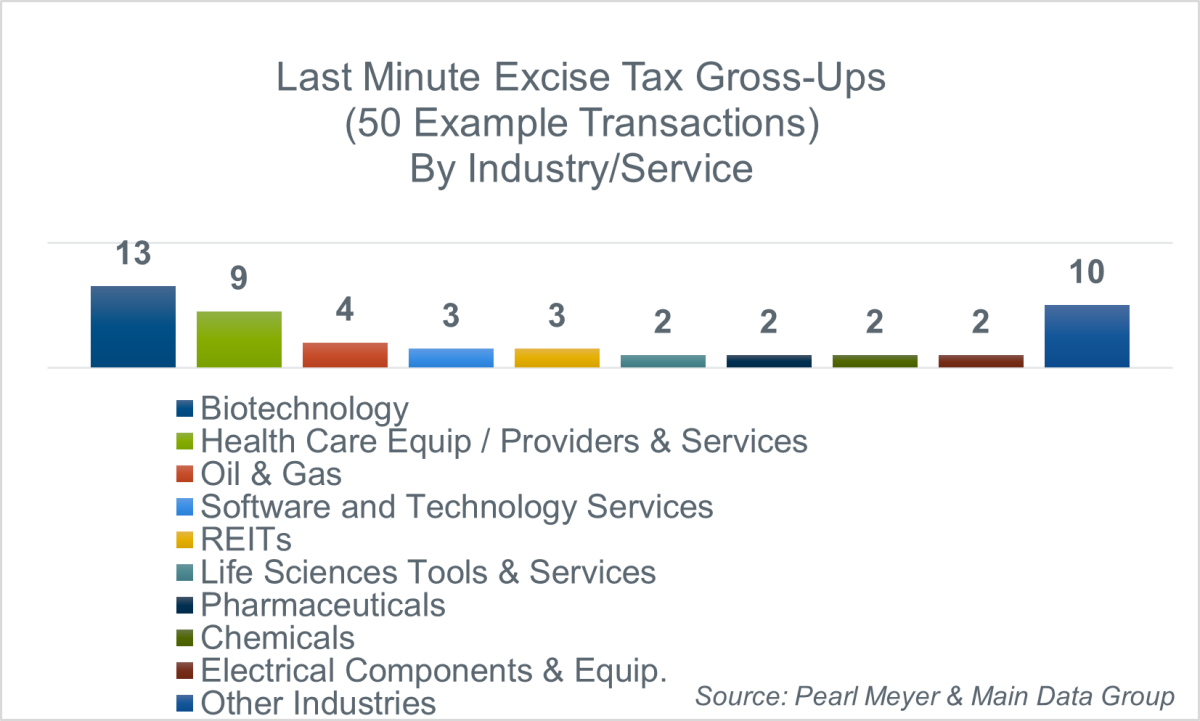

The companies approving last-minute gross-ups spanned various industries and services. Biotechnology companies and healthcare equipment and/or service providers had the most instances of implementing them (13 companies and 9 companies, respectively). Of the 10 transactions that were not required to have a SOGP vote, nine were biotechnology companies.3

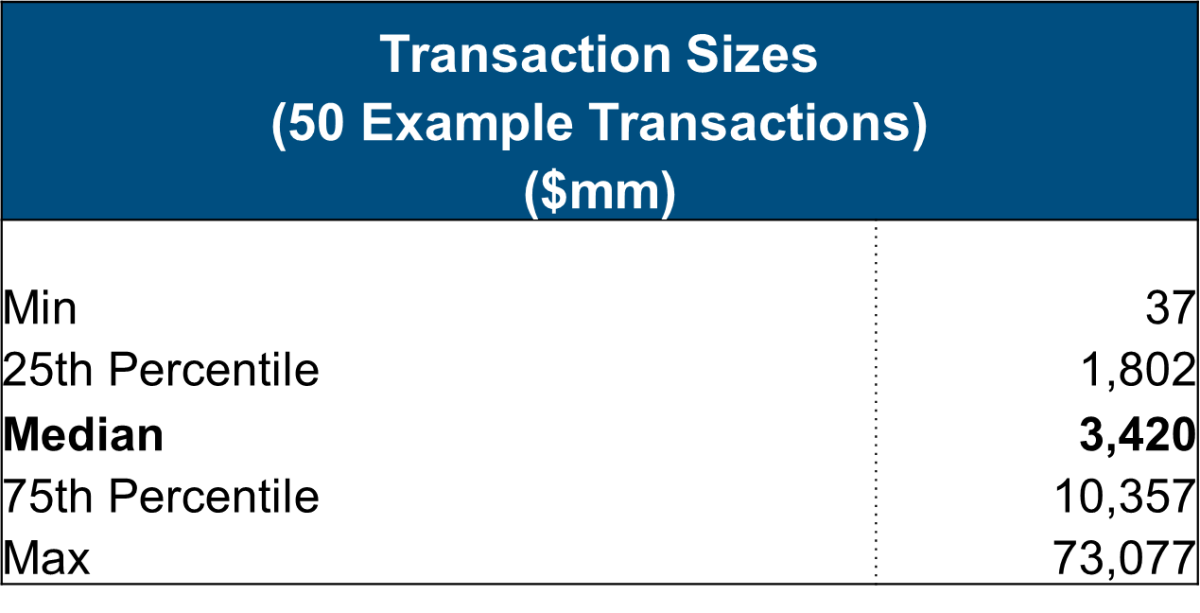

The size of the deal doesn’t appear to affect company decisions about providing last-minute gross-ups. Transaction sizes4 of the 50 companies spanned from $37 million to $73.1 billion; the median and 75th percentile transactions were $3.4 billion and $10.4 billion, respectively.

Totals and Types of Golden Parachute Payments

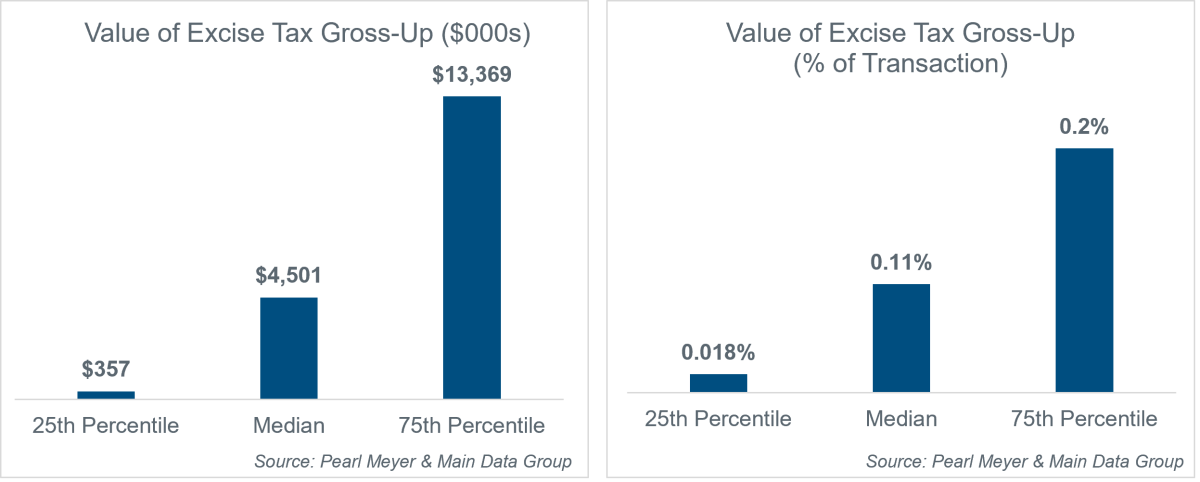

In the 50 example companies, the total of all golden parachute payments (including excise tax gross-ups) payable to executive officers varied significantly in dollar values relative to a percentage of the transaction value. The value of the excise tax gross-ups provided in these cases also varied substantially.

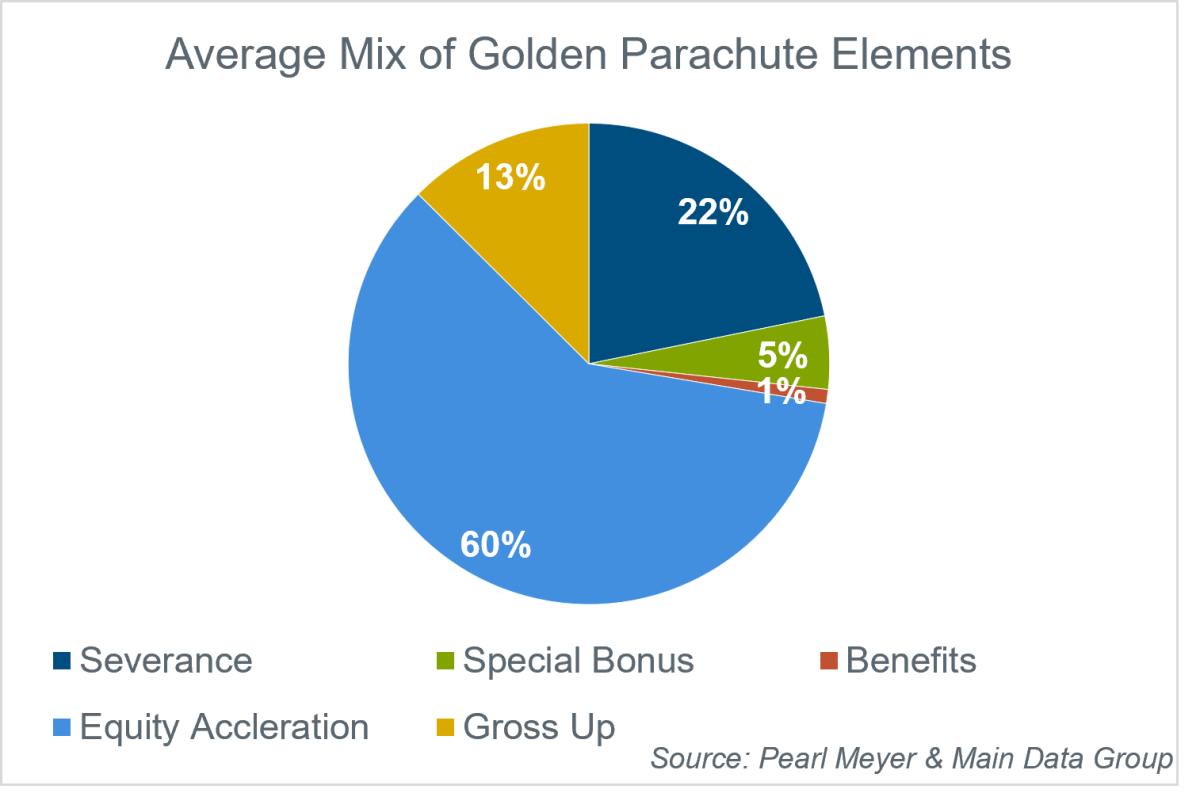

While the costs of the excise tax gross-ups were significant, they were not nearly as significant as the value of accelerated equity, which represented the largest component of the total golden parachute packages.

Excise Tax Caps

In a likely effort to reduce and fix costs, 15 of the 50 companies put limits around the total gross-ups they would pay to all executives in the aggregate. These caps ranged from $1 million to $35 million.

Rationale for Implementation

The majority of companies making last-minute excise tax gross-ups (66%) did not provide reasons for implementing them—perhaps hoping to avoid excessive attention.

Among the minority of companies that offered their insight, we found three common justifications:

- Consideration for Restrictive Covenants. The excise tax gross up was provided in consideration for entering into a restrictive covenant agreement where executives would be subject to non-competition and non-solicitation provisions for a period of time after the transaction and their terminations.

- Alignment with Shareholders. The value of equity acceleration, driven by the deal price negotiated by executives, represented the majority of the golden parachute payments. Securing the best price was in the best interests of shareholders and the 280G excise tax imposed on executives was punitive compared to the ultimate value delivered to shareholders.

- Retention. Special arrangements were needed to retain key executives during the transition period following the CIC.

Impact of Last-Minute Gross-ups on SOGP Vote Results

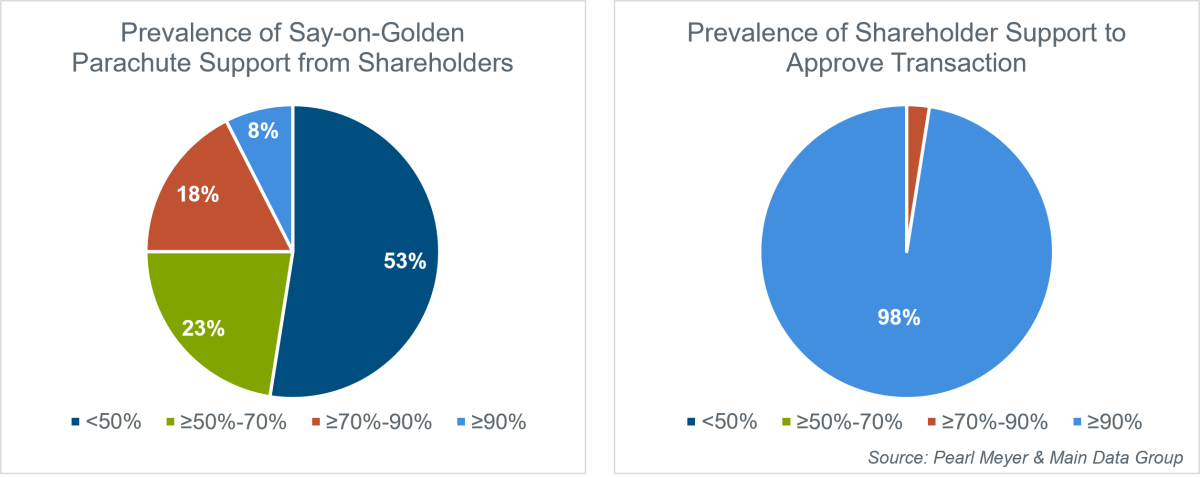

As mentioned, in 10 of the companies that had implemented 280G gross-ups, no advisory SOGP vote was required in the transaction process. However, in the remaining 40, the transaction required a shareholder vote. In these transactions shareholders were much less supportive of the golden parachute payments than they were for the transactions themselves: 93% of these companies received less than 90% support in the SOGP vote—in fact, over half (53%) of the companies failed to receive 50% support. Conversely, shareholders provided overwhelming support for the overall transactions. The average vote to approve a transaction in this group was 98%.

Given these results, boards approving new excise tax gross-ups should be well aware that the SOGP advisory vote may ultimately fail.

Conclusions

A minority of companies in the study group of transactions implemented excise tax gross-up provisions in connection with impending transactions. Biotechnology companies and healthcare equipment and/or service providers had the most instances of implementation. However, most of the companies in the study group (96%) did not provide any new gross-up protections.

When approved, excise tax gross-up costs (as a dollar value and as a percentage of the transaction value) were significant. As a means to limit and fix the associated liabilities, some companies disclosed dollar limits on the protections provided.

Over half of the example companies that implemented last minute gross-ups failed the SOGP advisory vote. Despite the negative repercussions, SOGP disclosures provide a glimpse into the reasoning for the minority of companies that approved them. In the transaction setting, excise tax gross-ups have served as consideration for non-compete restrictions, retention vehicles, and a means to align management with shareholder outcomes. An additional explanation for the varying practices may relate to an organization’s history. Mature, stable organizations are better able to thoughtfully plan for CIC contingencies; their executives are also more likely to have received the benefit of short-term and long-term incentive payouts, thus improving their 280G results. High growth companies, by contrast, may have limited historical compensation, increasing the likelihood that executives will owe 280G excise taxes. For boards of these companies, inaction might be viewed as punitive to the executives who have created significant shareholder value.

The decision as to whether to provide an excise tax gross-up is a sensitive one. Companies implementing these should expect lower SOGP results by doing so. In addition, legal advisors may express concerns that implementing these types of provisions may further encourage shareholder lawsuits that so often accompany transactions. Boards must weigh whether the benefits to shareholders will ultimately outweigh the costs as part of their fiduciary oversight.

[1] See the 2018 article “Think the Tax Gross-Up is Obsolete? Not Necessarily” for background on Internal Revenue Code Sections 280G and 4999, excise tax gross-ups, and their historical decline.

[2] Pearl Meyer and Main Data Group reviewed and summarized over 900 SOGP disclosures filed from January 2016 through April 1, 2022.

[3] One pharmaceutical company was also not subject to the SOGP vote.

[4] Transaction sizes reflect transaction equity values reported by Capital IQ.