Advisor Blog | Feb 2019

Economic Value Added is a Shortcut That Doesn’t Consider Nuance

Our survey data show that while ISS is very interested in EVA, investors are not. We explore why that is likely the case.

The proxy advisor ISS has signaled its intent to include Economic Value Added (EVA) measures as a cornerstone of its quantitative pay-for-performance screens, leading companies to revisit the relevance of EVA as an incentive plan measure.

EVA is an established standard for estimating a firm’s economic profit, or the value created in excess of the required return of a company’s shareholders. It is commonly calculated by subtracting a “capital charge” (i.e., the cost to the company of providing an acceptable return to all capital providers, including equity owners and debt holders) from Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT).

ISS has asserted “EVA provides a standardized view of economic performance, versus accounting results, by applying a series of uniform, rules-based adjustments to financial statement data. Those adjustments improve comparability of companies across different industries. They allow for comparisons of firms with different operating models and/or capital structures as well as companies at different points in their business cycles.”

ISS will phase in EVA measures as a display item in its research reports during the course of the 2019 proxy season (i.e., annual meetings on or after February 1, 2019). The proxy advisor has indicated it “will continue to explore the potential for future use of Economic Value Added (EVA) measures to add additional insight into a company's financial performance.” Presumably such future use would include use of EVA as either a supplement or replacement to current financial performance assessments that consider an issuer’s performance with respect to ROIC, ROA, ROE, EBITDA growth, and/or cash flow growth, depending on industry.

Naturally, these moves have sparked interest from compensation committees and management teams as to whether EVA concepts ought to be included in their own assessments of company performance. The key question: “If there is indeed an emerging consensus that EVA concepts are effective for managing a business and making peer comparisons, ought EVA measures be embedded in executive incentive programs?”

In this climate, we are curious to understand whether investors are truly signaling to our clients that they would like to see EVA measurement protocols drive incentive payouts.

Survey says…

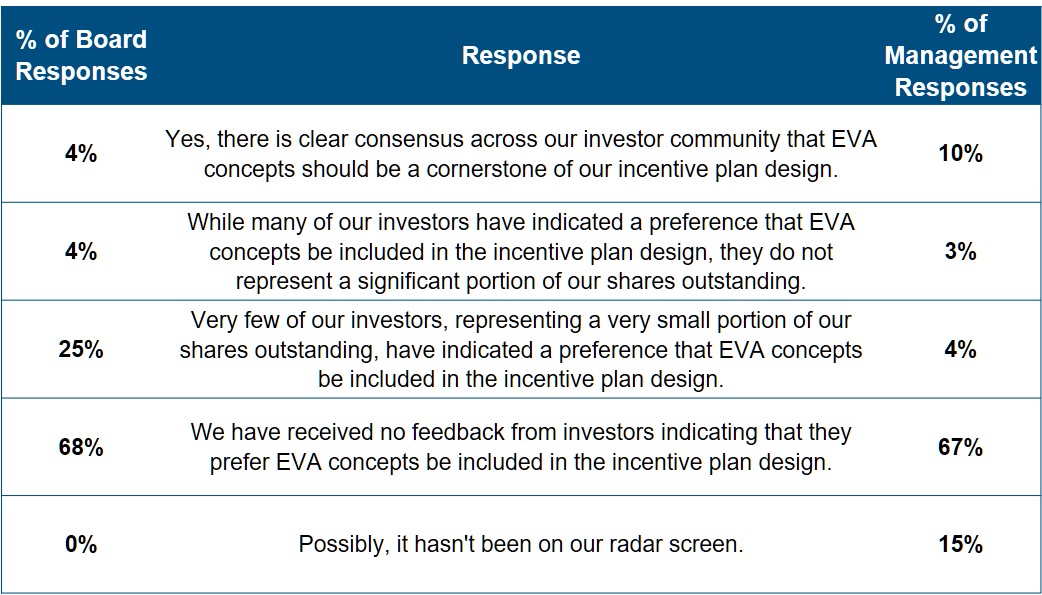

Fortunately, our Quick Poll series Setting the Compensation Committee Agenda is designed to challenge and explore whether items that appear to be capturing public attention—for good or ill—translate into actual time spent in review and discussion at compensation committee meetings. This winter we asked participants a simple question: Have your investors requested a strong emphasis on Economic Value Added measures for your executive incentive plans?

We received 95 responses, detailed below:

We find it interesting that:

- A clear majority (68% of board respondents and 67% of management respondents) affirm that they have received absolutely no feedback from investors advocating inclusion of EVA concepts in the incentive plan design.

- The small minority (4% of board respondents and 10% of management respondents) who do indicate that EVA concepts are advocated by their investors represented a cross-section of industry sectors and company sizes; in other words, there seemed to be no easy explanation of “investors in sector ___ are gravitating towards EVA concepts.”

Why are investors not embracing EVA as a measurement tool?

In our experience, institutional investors have never been shy about communicating to companies how they intend to evaluate performance and EVA very rarely comes into the conversation. This is not to say that EVA, and the concept of economic profit, are not valuable tools for corporate planning. It is more that, for compensation design and pay-for-performance evaluations, EVA presents at least as many challenges as advantages.

We believe that EVA is a shortcut that doesn’t consider nuance.

A better methodology would tailor the performance lens based on sector-specific, cycle-specific, stage-specific, and even company-specific factors. If EVA actually reflected these dimensions, we would see EVA more widely embraced across sectors.

For example, it would be inappropriate to compare EVA between two comparable organizations where one is engaged in an acquisition strategy or has embarked upon a large capital project. Furthermore, cost of capital is a function of balance sheet management. Therefore, a company that has an acquisition will appear worse from an EVA standpoint in the short term (e.g., three years) as compared to a company that buys back stock.

As another example of nuance, comparative performance becomes very difficult when EVA is close to breakeven (zero) in a given period. Very small changes in growth, profitability, and/or capital employed can have a very large impact on EVA metrics, driving positive metric results to negative and vice versa. These large swings too often provide a signal in conflict with sound long-term management. Again, company-specific context is critical.

For these reasons and others (including complexity), EVA is not market practice in designing incentive compensation plans. While we agree that EVA and the concept of economic profitability is important to long-range planning and decision-making, we do not see it as a good, broad-based yardstick for assessing CEO pay-for-performance.

So why does ISS have such interest in EVA?

Upton Sinclair made a useful assessment that (unlike EVA) tends to accommodate the complexity demonstrated by distinct sectors, cycles, and companies:

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

In 2018 ISS purchased EVA Dimensions, a consulting firm that “provides software and training and support services that automate the best practices in EVA.” Incorporation of EVA-related measures as a component of ISS pay-for-performance assessments immediately provides a patina of credibility to EVA-related tools. It would also presumably drive demand for EVA Dimensions services, especially once EVA-derived scores are reported (and in some ways, marketed) in the research reports that ISS distributes to its clients.

ISS promotes its EVA platform to investors here.

What your committee should discuss in Q1 when it’s not discussing EVA

One of our goals for this Quick Poll series is to provide regular guidance on areas that may not be attracting public attention but are still important, timely, and merit committee consideration. Having (hopefully) provided comfort that most companies need not completely revamp their incentive programs following the ISS-triggered renewed interest in EVA, we have a few suggestions on where time might be spent instead.

For December fiscal year-end companies, Q1 is typically dedicated to determining year-end pay decisions (incentive plan payouts for prior year performance, calibrating goals for new performance periods, and setting base salaries for the coming year) and, for publicly traded companies, preparing pay disclosures including the Compensation Discussion & Analysis section of the Annual Proxy Statement. We suggest:

- When calibrating goals for 2019 and beyond, give real consideration to the implications of a possible downturn. The US economic expansion began in July of 2009 and is now close to the longest on record. Among the many compensation-related issues that take on an increased sense of urgency in the midst of a recession, goal calibration and balancing the tension between retention and pay-for-performance alignment are near the top. Companies should have a consistent practice of modeling downturn scenarios when examining any program design—and may also wish to spend time having candid discussions between management and the committee with respect to what possible tools that may be employed in a downturn (e.g., adjustments to performance targets, use of cash retention bonuses) and in what scenarios those tools should or should not be under consideration.

- When preparing round two of CEO pay ratio disclosures, this checklist will be useful.

- If using the same median employee identified in 2017, the disclosure must still contain:

- Updated ratio numbers using 2018 Summary Compensation Table number for the median employee and CEO;

- A statement that there was no material change, so the company continues to use the same median employee as identified in 2017; and

- A description of the methodology used in 2017 to identify median employee.

- Determine whether there was a material change in the employee population or compensation programs:

- If so, determine whether that change is reasonably likely to change the pay ratio in a material way;

- If it is reasonably likely, the median employee should be re-identified, and the methodology for 2018 should be updated for 2018; and

- If it is not reasonably likely, the company may use the same median employee and follow steps in #1, above.

- If the company excluded employees as a result of acquisitions in 2017, it should go through the exercise in #2 to determine if inclusion of the acquired employees this year would materially impact the pay ratio. If the answer is “no”, the company need not re-identify the median (and again, follow steps in #1, above and include disclosure explaining why methodology did not change).

- If re-identification of the median employee is not needed this year, is the 2017 median employee still employed or was there any material change to his/her compensation? If so, the company should go through the exercise of choosing the closest median off the list from last year (along with disclosure that states why the company had to do so).

- Were there any significant changes to CEO compensation that will materially impact the ratio? While that would not require the company to re-identify the median employee, it may generate some discussion about whether additional disclosure should be introduced to explain the difference (e.g., new CEO, one-time grant, etc.).

- If using the same median employee identified in 2017, the disclosure must still contain: