Article | Oct 2018

Four Operating Principles for Developing Resilient Executive Compensation Programs

How boards can accommodate the potential for unforeseen risk in their executive pay programs.

Editor's Note: Pearl Meyer is a strategic content partner for the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD). Pearl Meyer is an active participant each year on the NACD Blue Ribbon Commission (BRC) and contributor to its annual BRC reports—signature publications that propose new principles and practices to address the most critical boardroom issues. The following article was published as an appendix in the 2018 BRC report Adaptive Governance: Board Oversight of Disruptive Risks.

Enterprise risk management can be incorporated into an executive compensation program by an astute and forward-thinking committee. However, by its very definition, atypical risk cannot be foreseen. Boards who adopt an adaptive and flexible governance approach are able to take the unknown into consideration and apply it to the very concrete reality of an executive compensation plan.

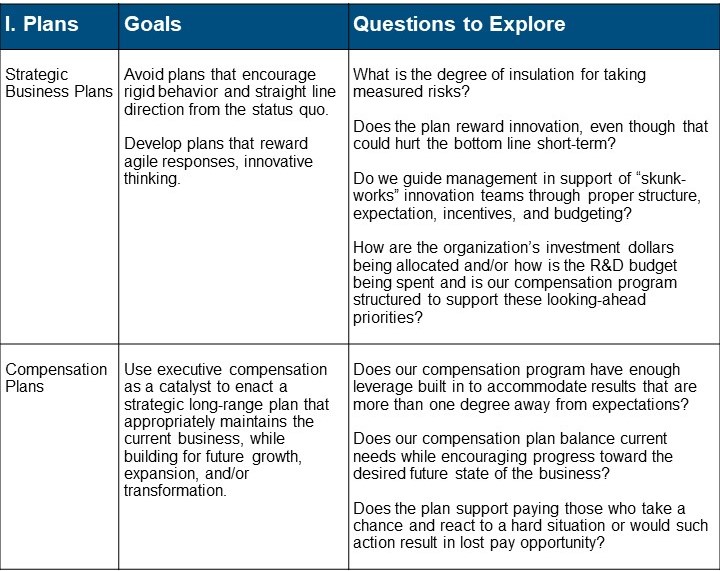

Pearl Meyer offers a set of operating principles based on plans, people, processes, and perspectives that can help compensation committees prepare to weather—and ideally capitalize on—the effects of a fast-changing business climate. Compensation committees can use this tool, including the guiding questions, to benchmark their current practices and identify opportunities for improvement.

I. Plans: The Strategic Business Plan and Compensation Design

An effective strategic business plan must deliver shareholder value based on the current state of the organization, while preparing for long-term changes to the future state. Strategic business plans must further accommodate an ever-changing environment of sharp turns in global economics, geopolitics, and social norms.

As market life-cycles speed up, there is also potential for changes to the compensation framework that ideally acts as a catalyst for the business plan. Courtesy of recent tax reforms, the constraints imposed by Section 162(m) on levels of executive pay and limits on the use of discretion are falling by the wayside. This will allow companies to make real-time changes to their compensation plans and ensure programs are keeping pace with an evolving business strategy or business circumstance. While the focus on alignment between pay and performance that 162(m) helped bring about will not be abandoned, the art and science of compensation design can generally be expanded.

The conundrum that boards face with disruptive, atypical risks is how to build flexibility into the compensation program while still adopting meaningful/measurable goals that align to an evolving business plan. Necessary questions are: Does the plan support paying those who take a chance and react to a hard situation? Does it reward innovation, even though that could hurt the short-term bottom line? Are the guardrails strong enough to ensure the company is not taking on unnecessary risk? Responding appropriately to atypical risk will probably require more discretion and may result only in long-term pay-for-performance and less short-term alignment.

Bear in mind that a pay plan that has the flexibility to accommodate unforeseen issues is likely going to be at odds with a plan that effectively manages for identified risk. A compensation structure that is aligned with a normal enterprise risk management process will naturally account for anticipated potential negative outcomes and thus may have program characteristics like narrow performance ranges with high thresholds, long life cycles, and traditionally defined clawbacks. Such a plan is purposefully geared to be conservative and not spend “too much” for “too little” performance. More flexible designs often couple committee discretion with a combination of pre-defined “adjusters” that can ratchet performance goals both up and down based on industry-relevant inputs (e.g., oil prices, consumer spending, etc.).

As plans are being determined, compensation committees should fully examine the tradeoffs and possible unintended consequences of their incentive design. Some examples include:

- Understanding the leverage curves (a steeper leverage curve provides stronger penalties/rewards for under/over achievement. Conversely, a shallower leverage curve better addresses performance volatility, but still may not adequately address unforeseen risk);

- Planning the time horizon of incentives (e.g., should there be shorter short-term incentive performance periods so the company doesn’t have to see as far into the future and/or should long-term performance periods be lengthened further to allow for capturing the uncertainty of the timing of events? Many small technology companies are using six-month performance periods while institutional investors are calling for companies to increase their long-term incentive performance timeframe beyond three years);

- Setting the pay mix (e.g., what is the relationship between the risk profile of your program versus target pay and how does it compare to peers? One would expect a program with higher risk to have greater payout opportunity);

- Calibrating the potential payouts relative to expected financial results (e.g., percent of revenue/net income) in addition to comparison to market pay levels;

- Timing the payout (e.g., quarterly versus semi-annually versus yearly and coinciding with the fiscal year-end of the company);

- Expanding the definition of clawbacks to account for atypical, disruptive risks; and

- Examining contracts for payout scenarios that may occur as result of atypical risks.

As the committee works to understand these implications, modeling various scenarios that could arise as a result of the technical program elements can be a useful exercise.

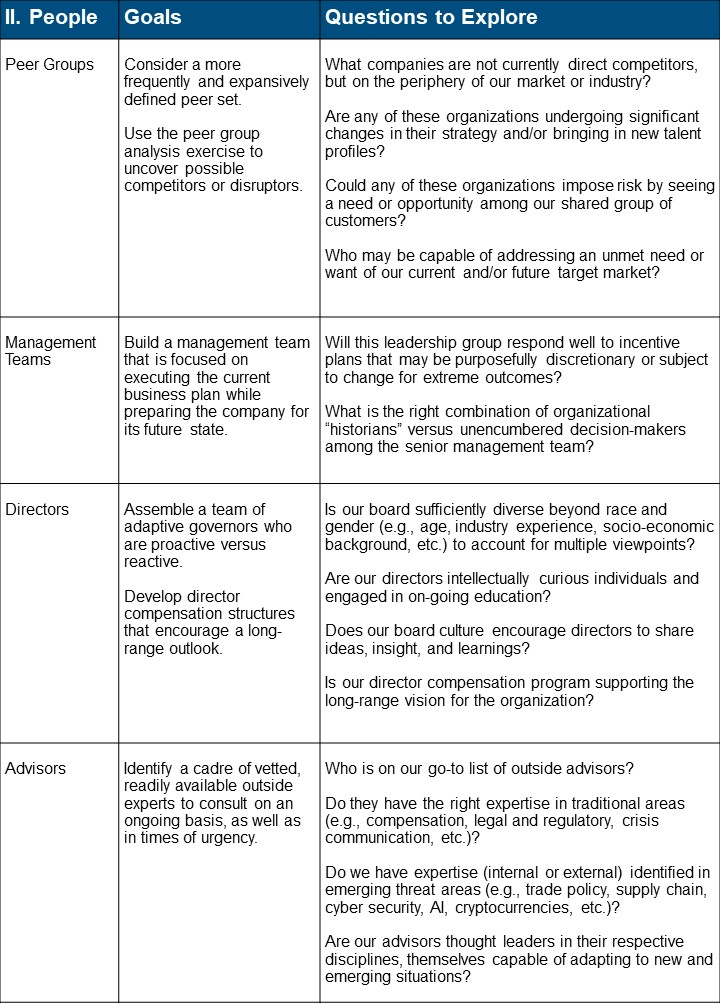

II. People: Peer Groups, Management Teams, Directors, and Advisors

While unintended self-sabotage does happen, the chances are very good that if a company is executing well and according to its planned strategy, any disruptive risk that threatens the business model or future growth will likely come from outside the organization. Should the threat arise from an outside enterprise (versus a situation that emerges from geopolitical pressure, a natural event, etc.), it is not likely to come from the “usual suspects.”

While stealth-mode start-ups will be hard to spot, boards—and compensation committees specifically—can address a portion of this external threat by expanding the peer group concept. Consider existing businesses that lie along the “right of way” of the current products and services. In other words, what organizations are not currently direct competitors, but are on the periphery of your industry and may be capable of addressing an unmet need of your shared customer base or end-market focus? Could any of these businesses impose risk by seeing a need or opportunity among this shared group of customers that your organization is missing?

Taking this core element of annual compensation planning—peer group selection—and making the exercise more frequent and expansive can help identify possible sources of disruptive risk. It can also result in thinking more broadly about the possible talent pool opportunities and the relative competitiveness of the executive compensation structure. (For instance, many companies in manufacturing are moving their future broad-based talent acquisition strategy from traditional machine operators to technologists.)

Meanwhile, that talent pool may ultimately be the best answer to a majority of the issues posed by unknown threats. Companies need a critical mass of individuals to impact change and therefore a large part of the board’s job (arguably with the compensation committee’s leadership) is to build a management team that can simultaneously execute the current strategic business plan and prepare the company for its future state. This team should also respond to change and enact transformation when needed. Are the incentives for this team encouraging, or perhaps unintentionally hindering, a management perspective that scans the environment for threat and opportunity? Is there sufficient trust between the board and management that potential problems are identified and discussed early on?

The board itself will benefit from “adaptive governors,” including directors who have successfully endured significant corporate upheaval or themselves been disruptors. Assessing and selecting board members who are anticipatory versus reactive will strengthen the oversight of the organization. (Although beware of “quick decision makers” who may actually be more knee-jerk in reactions as a response to stress.)

Recent news has provided ample illustration of the need for swift, decisive, and accurate response to a threat. Several companies this past year have faced high-profile and quickly accelerating issues with workplace harassment. At some level, both the boards and management teams probably believed this particular risk was well-managed through the traditional HR function, yet the sweeping nature of the #metoo movement has radically altered what was considered by many organizations to be a “known” risk. As a result, we’ve seen numerous companies scrambling in a very public way for appropriate responses. It’s likely many of these boards have had to consult outside experts for advice, but how many had those experts at the ready?

Boards can benefit from taking a proactive stance to recruiting the right advisory expertise. First, identify and designate individuals on the board who can confidently take the lead on certain types of issues based on their own experience, knowledge, and background, as well as their wider network of experienced contacts. Then, form a cadre of outside advisors and go-to experts. They should be thought leaders in their respective disciplines and have a demonstrated capability for delivering sound advice in rapidly changing situations.

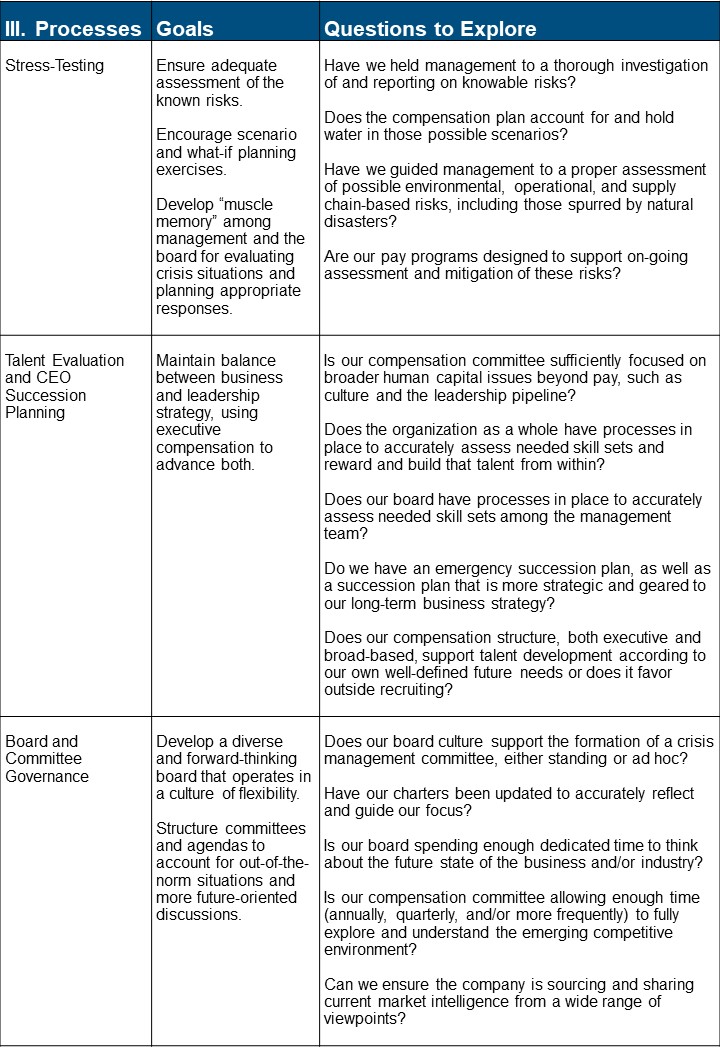

III. Processes: Stress-Testing, Talent Development, and Board Governance

In the course of business as usual, there are ways an organization can expand typical operations to become more future-oriented. Stress-testing existing compensation plans that have been constructed to account for ERM-related risks may highlight additional existing risk issues that weren’t previously considered. At a minimum, the exercise of stress-testing strategies and plans will help teams imagine alternative scenarios, potentially boosting the group’s ability to develop alternatives when faced with the unexpected.

This kind of brainstorming and ideas exchange can be a way to build organizational muscle memory and develop a culture of creative response when the unforeseen occurs. There are practical elements to consider in this exercise as well. For example, as part of the budgeting process, should the company fund contingent incentive pools for addressing unforeseen issues and if so, at what level? Has the compensation committee fully discussed how, when, and why it might need to use discretion in its plan?

As a committee, consider broadening the group’s focus beyond compensation. While that word is typically in the committee name, succession planning and leadership development also play a big role building the innovation culture of a company–and those processes are squarely in the purview of the compensation committee. For the talent development process, focus on the long-term strategy. If that strategy is achieved, what will the business look like and are the right people in place to run it? If not, are you developing the talent that’s needed, not to take over tomorrow, but to take over in five or 10 years?

Finally, don’t overlook how board and committee governance might enhance or inhibit the organization’s response to threat. Board workflow should be evolving with less time spent on compliance matters and more time expressly set aside for discussing and testing the future state of the business. Designating directors to play the role of “activist investor” or “devil’s advocate” on a rotating basis can provide much needed counterpoints for effective and comprehensive boardroom discussions on strategy.

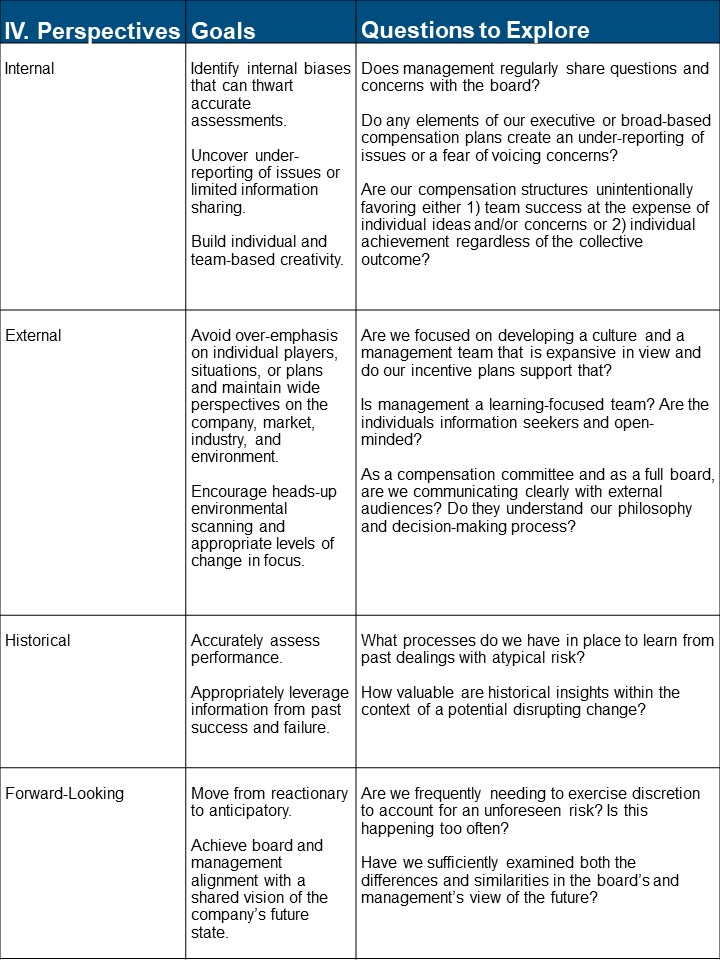

IV. Perspectives: Internal and External, Historical and Forward-Looking

There is safety in the familiar and many times as an organization looks inward, the default response to any question is to encourage the status quo. This is particularly true if business is going well. However, this default mode can result in a rigidity that can be hard to escape when the unexpected happens. If the board can guide management to a more open dialog that encourages sharing concerns and pulling in external environmental context, there may be less tendency to put an optimistic spin on either business as usual or outright problems. The compensation committee can examine whether executive compensation plans create an under-reporting of issues or a fear of voicing concerns.

Overall, the ability to manage the unexpected can come from a team that appropriately leverages information from past success and failure, while taking a stance that fully expects market change, even beyond what is currently quantifiable. The board can guide management, via conversations and incentives, to move from a reactionary stance to one that is anticipatory. The thoughtful use of both lagging and leading performance metrics, as well as examining the emphasis placed on legacy business lines versus new opportunities, are very effective tools to guide management’s perspectives.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Use of Discretion

Unfortunately, there are no customary design parameters that can entirely ensure your compensation program covers unforeseen risk. And while flexibility is a must, disruptive risks may demand responses that go beyond simply being accommodating. Surviving and thriving in the midst of a true black swan will require a quick-turn response and a willingness on everyone’s part to do something radical and outside the norm, not just something different than what was planned. At these times the organization’s plans, people, processes, and perspectives will converge.

The best-in-class compensation committee will ask: “Have we created a leadership team, an environment, and an executive pay structure that gives our board and this organization the flexibility—as well as the creativity and the confidence—to do what’s right, not necessarily just what’s documented on paper?” Directors that can answer “Yes” to this question have made a significant contribution toward building a resilient compensation program and an adaptable organization that truly aligns pay with performance.

Operational Principles: Guiding Questions for Directors